Galactosemia is a rare, potentially life threatening, autosomal recessive metabolic disorder in which patients are unable to metabolize galactose.1,2

Galactose, a simple sugar produced endogenously and gained through the diet in lactose-containing dairy products and also at lower levels through fruits and vegetables,3 is normally metabolized in the Leloir pathway. The enzyme galactokinase, also known as GALK, metabolizes galactose to galactose-1-phosphate (Gal-1p).

The enzyme GALT subsequently metabolizes Gal-1p1 to glucose-1-phosphate.

In Classic Galactosemia, patients either do not have GALT catalytic activity,1 or the GALT enzyme is completely missing.4

Both outcomes lead to the accumulation of Gal-1p and galactose.5

However, levels of Gal-1p do not correlate with clinical severity or long-term outcomes of Galactosemia and therefore Gal-1p is not considered to be the toxic metabolite of the disease.6 Instead, Gal-1p levels are useful for monitoring dietary compliance.7

Build-up of galactose and Gal-1p triggers the alternate polyol pathway, through which galactose becomes an aberrant substrate of Aldose Reductase, an enzyme that metabolizes galactose to the toxic metabolite, galactitol.8,9

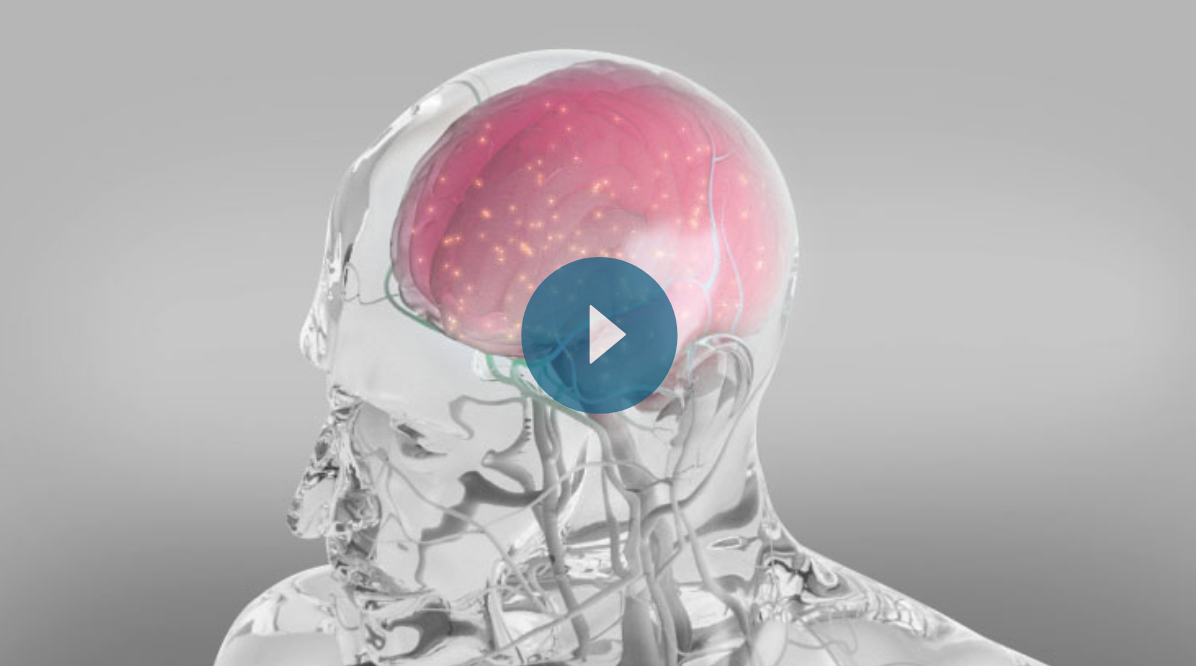

Galactitol cannot be reduced further by sorbitol dehydrogenase, the next enzyme in the polyol pathway leading to accumulation of toxic galactitol and subsequent disease complications throughout the body and organs, including the CNS.9,10

The majority of galactitol cannot cross the cell membrane, resulting in its accumulation in cells.4

The excess galactitol leads to an osmotic imbalance within cells that results in cell damage and cerebellar atrophy.10-12

Further toxicity is attributed to the redox dysregulation caused by galactitol, affecting neuronal function and compromising signaling capabilities.13

Symptoms of Galactosemia manifest shortly after birth following the consumption of breast milk or dairy formula.4

While dietary restrictions in newborns may prevent fatalities,4 these restrictions do not address the long-term complications of Galactosemia due to the endogenous production of galactose within the cell.2

Therefore, health issues are likely to persist and develop through to adulthood, including cognitive and intellectual deficiencies,8 speech delays and apraxia, cataracts,14 tremor,12 seizures,15 depression,16 fine and gross motor skill abnormalities,8 and primary ovarian insufficiency in females.8

As a result, adults with Galactosemia may find it difficult to live independent lives.

Research on the pathogenesis of Galactosemia has solidified understanding of galactitol as the primary toxic metabolite in the disease.

Galactosemia remains a disease with a high unmet medical need.17