This website uses cookies to help us give you the best experience when you visit and for certain analytics and marketing activities. By continuing to use this website, you consent to the use of these cookies. Please exit the website if you do not agree to such cookies being used. To find out more about how we use cookies, go to our Privacy Policy.

Classic Galactosemia

The pathway to understanding Galactosemia

Introduction

Galactosemia: A rare metabolic disease

Galactosemia is a rare, slowly progressive disease caused by a genetic inability to metabolize the sugar galactose. There are 2 subtypes of Galactosemia: Classic Galactosemia (or GALT deficiency) and Type II Galactosemia (or Galactokinase/GALK deficiency). Each type is caused by a different enzyme that does not work properly or is missing in the body. In healthy individuals, these enzymes are involved in metabolizing galactose. Classic Galactosemia and GALK deficiency can greatly affect development and quality of life, resulting in CNS complications, including deficiencies in speech, cognition, behavior, and motor skills. The CNS phenotype present in Galactosemia patients has been shown to progressively worsen over time with age. CNS deficiencies may emerge in early childhood as mild to moderate, but they often progress to severe deficiencies in later childhood and adulthood. Galactosemia also causes ovarian insufficiency in females, and it often results in ophthalmic complications, such as cataracts.1-3

Presently there are over 3000 individuals with Classic Galactosemia in the U.S. Most patients with Galactosemia are younger than 40 years of age, as newborn screening was not widely adopted until the 1980s. Galactosemia is now included as part of routine newborn screening in all 50 states in the U.S. and in many European countries.5,6

Mechanism of Disease

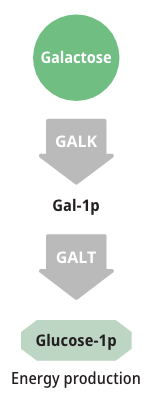

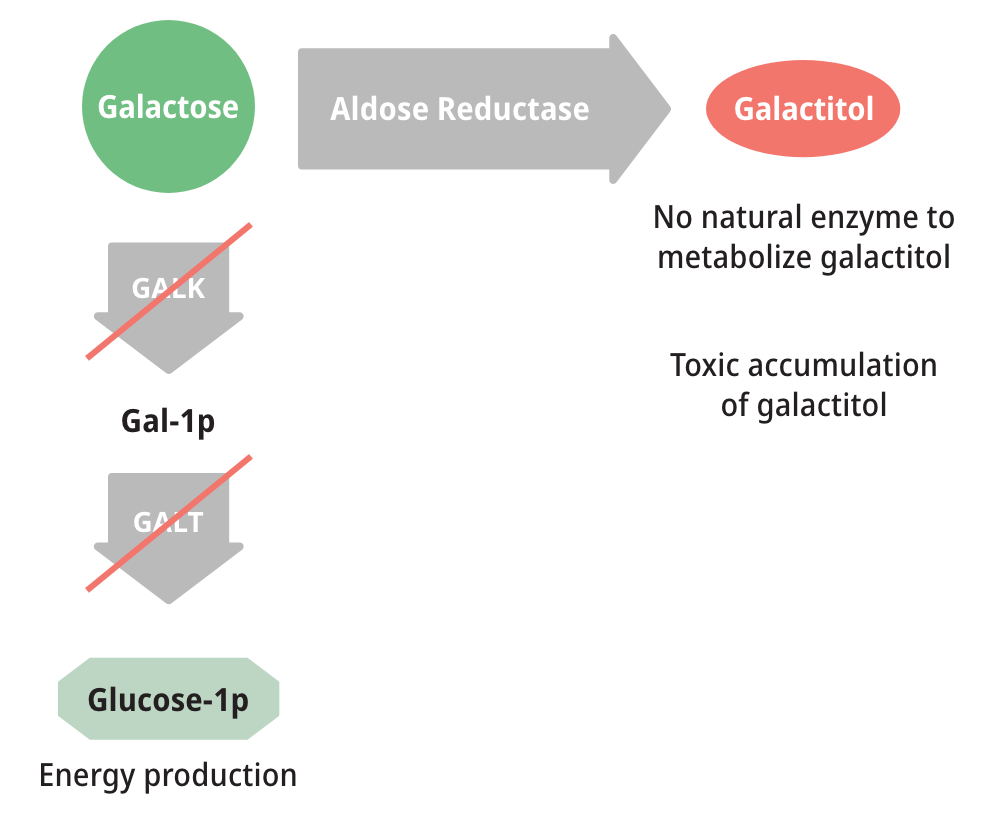

How galactose is metabolized

Patients with either form of Galactosemia are unable to metabolize galactose properly. As a result, galactose accumulates in blood and tissues. At abnormally high levels, galactose becomes an aberrant substrate for the enzyme Aldose Reductase and is converted into an abnormal and toxic metabolite called galactitol, which has been shown to cause the long-term complications of Galactosemia.6,8,9

Measuring galactose-1-phosphate (Gal-1p) is useful in monitoring diet compliance, but Gal-1p levels do not correlate with the clinical severity of Galactosemia.6,9

Toxic galactitol has been linked to long-term complications, including2:

These long-term complications are due in large part to endogenous production of galactose, which contributes significantly to the total free-galactose pool.7

Endogenous galactose production is thought to be a major factor in the pathogenesis of complications and accounts for the elevation of galactose metabolites in patients with Galactosemia; therefore, dietary galactose restrictions alone are not enough to manage Galactosemia.11

Galactose Sources

The 2 sources of galactose and their risks in Galactosemia

The total pool of galactose is composed of exogenous (dietary) and endogenously produced galactose. Endogenous production of galactose is 10x higher than that found in a restricted diet.7

Timely introduction of a galactose-restricted diet can prevent or resolve acute symptoms in infants with Classic Galactosemia. Yet despite early dietary intervention, patients still experience 1 or more of the long-term complications associated with this disease.2,7

Patients living with Galactosemia have historically been advised to undertake a more severe dietary restriction of galactose. However, as the body produces 10x more galactose than that found in a galactose-restricted diet, recent studies have found no significant association between dietary restrictions and long-term outcomes.7,12

Management

Dietary restriction alone is not sufficient

Currently, the only method of managing Galactosemia is timely implementation of a galactose-restricted diet. Galactose is found in dairy products, dairy-based infant formula, breast milk, and many fruits and vegetables. However, galactose is also endogenously produced by the body through de novo synthesis, so long-term complications continue to worsen despite strict adherence to a restricted diet. Dietary restriction alone is not sufficient to prevent progression of long-term disease complications.7

References

- Galactosemia. MedlinePlus US National Library of Medicine. Updated August 18, 2020. Accessed September 18, 2020. https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/galactosemia/

- Forges T, Monnier-Barbarino P, Leheup B, Jouvet P. Pathophysiology of impaired ovarian function in galactosemia. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12(5):573-584.

- Demirbas D, Coelho AI, Rubio-Gozalbo ME, Berry GT. Hereditary galactosemia. J Metabolism. 2018;83:188-196.

- Berry GT. Classic galactosemia and clinical variant galactosemia. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al, eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington; February 4, 2000.

- SHA Patient Transactional Dataset, February 2017 – January 2021 (Data on File).

- Coelho AI, Rubio-Gozalbo ME, Vicente JB, Rivera I. Sweet and sour: an update on classic galactosemia. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2017;40:325-342. doi:10.1007/s10545-017-0029-3

- Bernstein LE, van Calcar S. The diet for galactosemia. In: Bernstein L, Rohr F, Helm J, eds. Nutrition Management of Inherited Metabolic Diseases. Springer; 2015:285-293.

- Coelho AI, Trabuco M, Ramos R, et al. Functional and structural impact of the most prevalent missense mutations in classic galactomsemia. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2014;2(6):484-496. doi:10.1002/mgg3.94

- Berry GT, Hunter JV, Wang Z, et al. In vivo evidence of brain galactitol accumulation in an infant with Galactosemia and encephalopathy. J Pediatr. 2001;138(2):260-262.

- Welling L, Bernstein LE, Berry GT, et al. International clinical guideline for the management of classical galactosemia: diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2017;40(2):171-176. doi:10.1007/s10545-016-9990-5

- Berry GT, Nissim I, Lin Z, et al. Endogenous synthesis of galactose in normal men and patients with hereditary galactosemia. Lancet. 1995;345:1073-1074.

- Frederick AB, Cutler DJ, Fridovich-Keil JL. Rigor of non-dairy galactose restriction in early childhood, measured by retrospective survey, does not associate with severity of five long-term outcomes quantified in 231 children and adults with classic galactosemia. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2017;1-9. doi:10.1007/s10545-017-0067-x